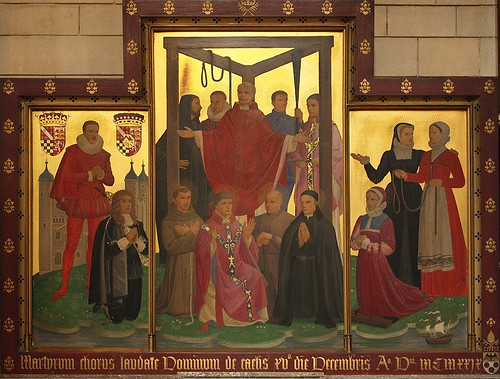

This week we celebrate the feast of the martyrs of England and Wales. Between 1535 and 1681, several hundred Catholics were executed for the faith, under the penal laws in England. There were various alleged causes, usually a spurious allegation of treason, but the majority suffered for their love of the Holy Mass, and a large number of those martyred were young priests who had trained secretly abroad, to come on the mission to England, knowing that they did so at risk of their lives. The first martyr of 44 from the English College in Rome, St Ralph Sherwin, was asked to sign the missionary oath that he would not hang around in Rome but return to England to preach the faith secretly. He signed the Liber Ruber, the “red book” with the addition potius hodie quam cras, “rather today than tomorrow.”

The stories of the martyrs’ heroism were preserved by contemporary writers, and later, many were set in order by the great Bishop Challoner who organised and cared for the Church in England and especially in London and the South during the difficult years when Catholics were no longer put to death but suffered debilitating discrimination, not being allowed to enter the universities or the professions, or even freely to leave their property to their family when they died.

Just one example of the events he recorded for posterity in his Memoirs of Missionary Priests was the Mass celebrated by St Edmund Gennings in the upstairs room of a Catholic house in Holborn on the Octave day of All Saints in 1591. During the Mass, Topcliffe, the arch-priest-catcher burst into the room. To prevent the desecration of the Blessed Sacrament, one of the men threw Topcliffe down the stairs and fell with him. St Polydore Plasden, another priest, blocked the door, but Topcliffe came up again with his officers. He was told that once the Mass was finished, they would come quietly, but they were determined to defend the Holy Eucharist from profanation if they tried to break in before then. They gave themselves up and with the exception of one woman, all the ten present at Mass were martyred, Fr Gennings with particular brutality.

Pope Paul VI made sure that the three women martyrs were remembered by including them in his canonisations in 1970. They suffered particularly for aiding or sheltering priests and for making it possible for Mass to be celebrated. A watchword that continued in common parlance in England was “It is the Mass that matters.”

We should be inspired by the history of those who kept the faith alive in dark times, and celebrate the glory that they share in heaven. Their stories are an important part of the history and culture of our country which impartial historians are rediscovering today. It behoves us to celebrate their holiness and valour. The English Martyrs also teach us to love the Holy Mass in which Our Lord is offered and received, and to give it the greatest priority in our lives.